The Klamath River is the lifeline for the Yurok, California’s largest Native American Indian tribe. In 2021 the four dams along the river which have affected the tribe immeasurably and caused considerable damage to the local ecosystem, will begin to be removed carefully, allowing the water in these beautiful coastal redwood forests to come alive once more and breathe life back into the area, whilst reenergising the Yurok people.

The Yurok’s story is an unfortunately all to common story within Indigenous communities, it’s one of community, oppression, suffering and fighting back, a story about nature and mans footprint.

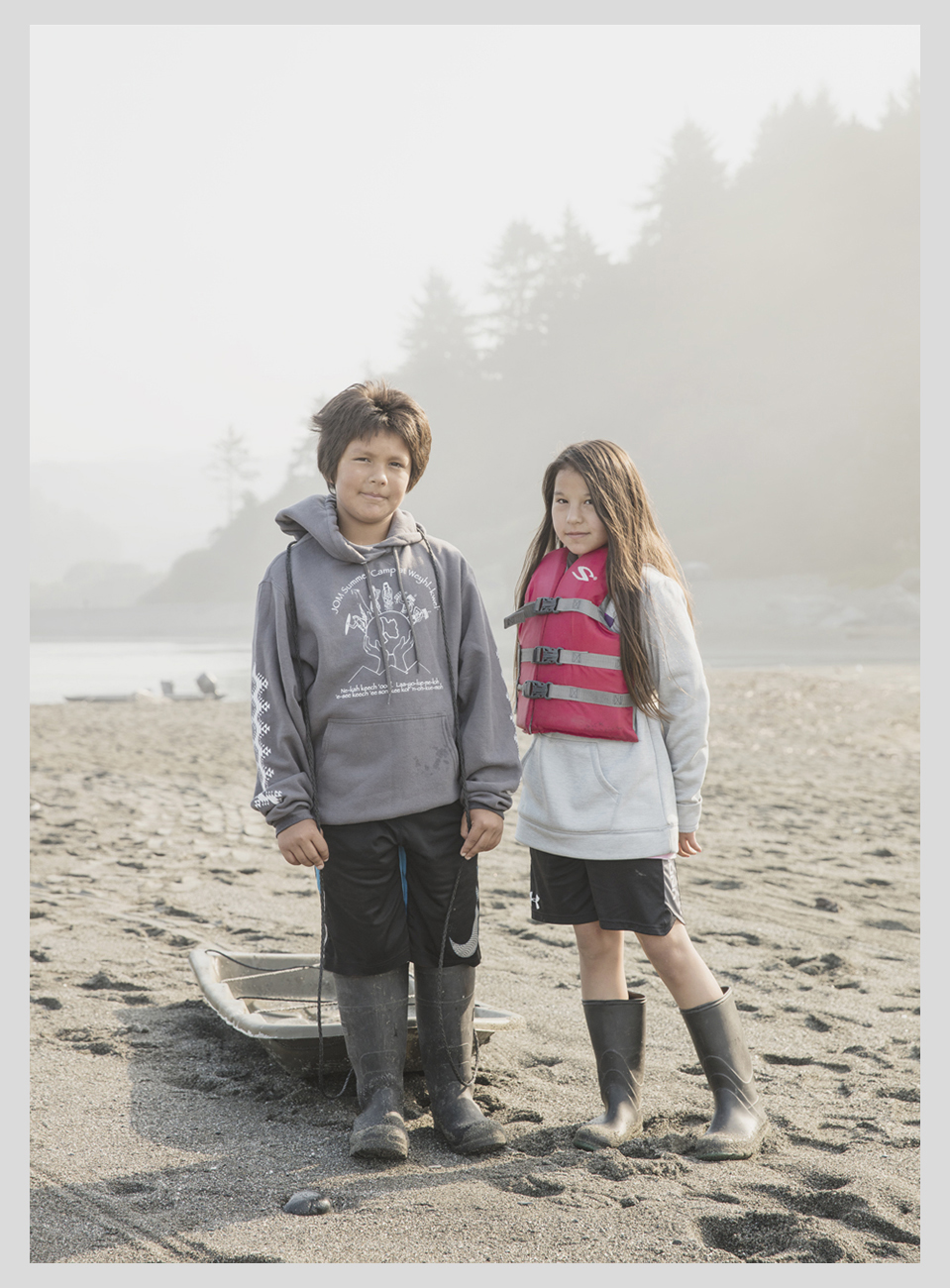

The Yurok are spiritually connected to the salmon run whose yearly migration is pivotal to their ancestral culture. The dams have had a major impact to such an extent that salmon fishing has been banned with only small catches allowed for subsistence. The Yurok tribe as well as other Native American tribes along the Klamath River have fought for decades to tear down the dams. That fight will finally come to an end in 2021, when salmon will once again have access to hundreds of miles of historic, spawning habitat.

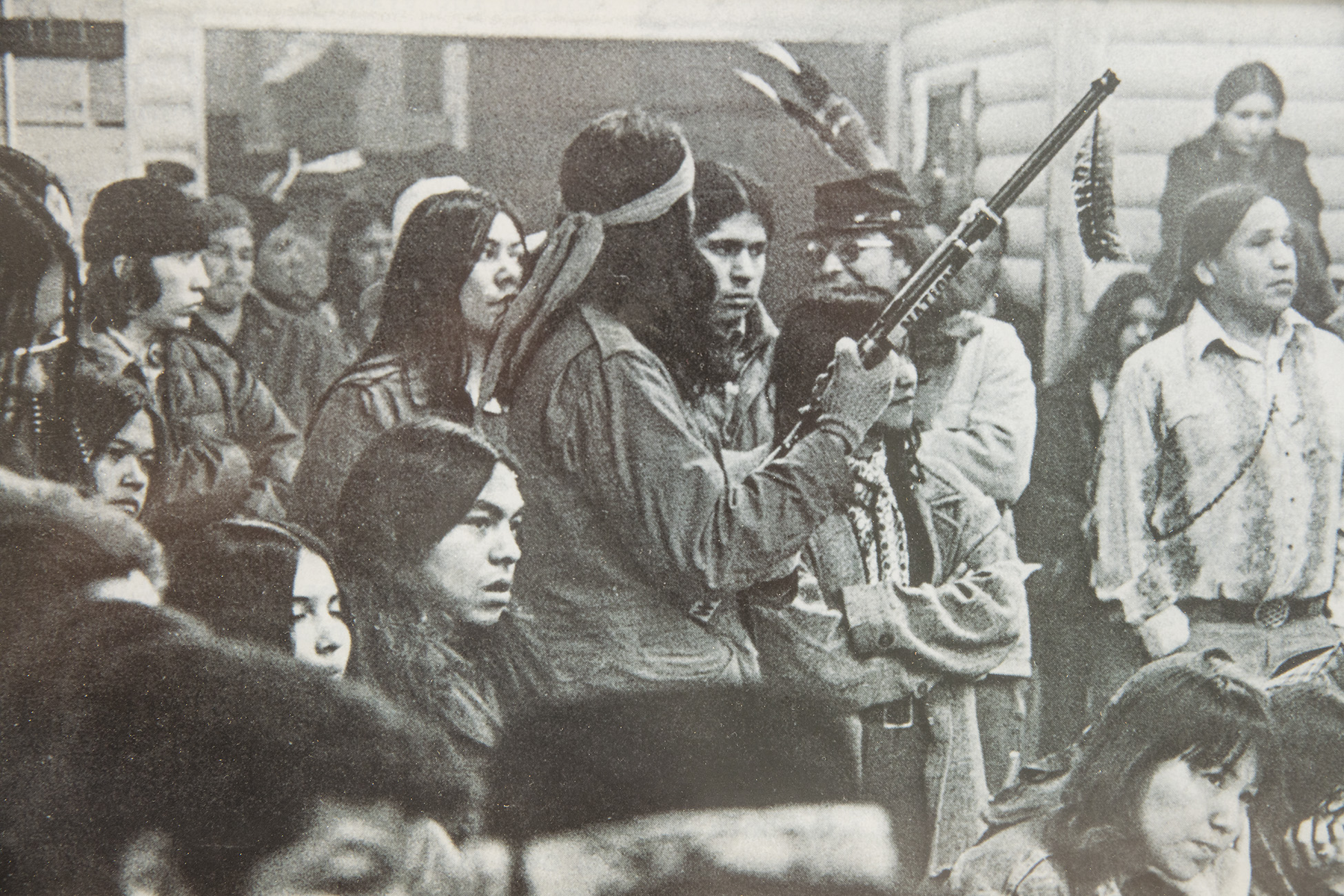

Native American communities have suffered immensely for generations, lives have been lost, land has been taken or devastated, communities have been lied to or they’ve been on the wrong end of numerous broken promises.

Yurok Tribal Chairman and Spiritual Leader Thomas O’Rourke recount’s some historical atrocities, and whilst referencing the past tries to make sense of their predicament. “ So we went through a period of, I guess you would say, a loss of identity, which leaves major voids in any individual that this has ever happened to. “ He goes on to talk further “ We’re born to fish, we’re born to hunt, we’re born to gather, we’re born to carve and make boats. We’re born to be on the water and on the land. That’s where we spent our days. That was our school. “ Thomas reflects more on the environment and the land. “ We’re here to maintain balance, only through balance can we insure or have the biggest of insurance that there is going to be a tomorrow. Our lands have been raped from it’s resources, our waters have been polluted, our people have been scattered, the time of destruction in our land has come to an end and it is time to restore. “

With dam removal just around the corner, the Yurok have already begun to turn things around and this is in large part to a global first. The Yurok Tribal Council decided to participate in the California Cap and Trade carbon market, making it possible to generate funds for the protection of their lands. This scheme was not always universally popular amongst the tribe as the scheme involved a suite of concessions to the state government, including a nominal loss of sovereignty and greater environmental oversight. A common argument against Cap and Trade is it’s potential to allow polluters to pollute as they offset their environmentally harmful emissions by purchasing carbon credits within the Cap and Trade program from forest communities such as the Yurok. Though on the other hand this significant new income stream has allowed them to appropriate lost cultural ceremonial items and buy back a river system vital to the salmon run.

The Cap and Trade program has been touted by environmental organisations as a possible model for other indigenous groups living in forests around the world to regain their rights, while working with national and provincial governments to combat climate change. Seven other indigenous entities in the US are now selling carbon offsets.

If industries keep slashing and burning the world’s rainforests at the current rate, the chance that countries will meet the Paris Climate Change Agreement goals of limiting global warming to more than two degrees Celsius rapidly plummets. Improving forest management and protections, on the other hand, could reduce emissions by an amount greater than vaporizing every car in the world.

The California Cap and Trade Program has allowed the Yurok to buy back areas of their land along the Klamath River, though many rightfully argue that these lands were stolen from the tribe during colonisation, people were murdered and persecuted in the process, and this land as opposed to being bought back should be given back to these communities.

The Yurok Tribes Self Governance Director Javier Kinney talks about how there was a compromise, and while it worked for the Yurok Tribe, that didn’t mean it was going to work for everyone. What mattered was “the tribes have a seat at the table,” he said. “We need to be decision makers in the management of our natural resources. That’s our main objective.”

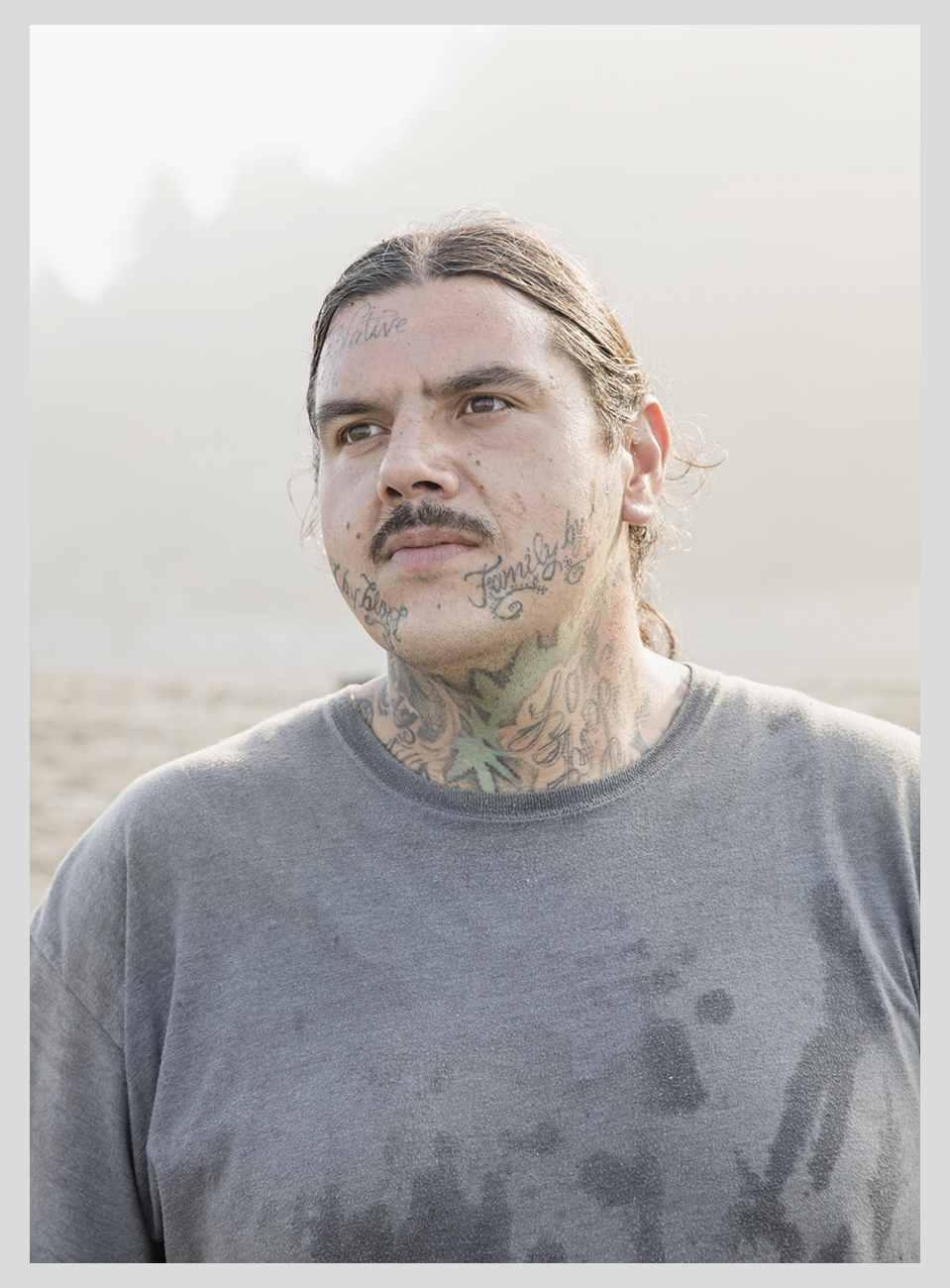

Whilst the Yurok Tribe has many reason’s to feel optimistic and positive as a community, with progression under Cap and trade and the soon to be decommissioning of the dams in 2021, they’ve suffered immeasurably like other Native American communities. It’s a long process of healing and recovery for the Tribe, socially and economically these are still difficult times as the youth in particular look to understand who they are and forge a path for themselves with limited role model’s and opportunities.

Though the Yurok has matched its words with action, setting up community groups to tackle the devastating issues affecting them and their youth, as well as campaigning rigorously to have the dams decommissioned and endeavouring to restore balance to the ecosystem, which is such an intrinsic part of who they were and are. They’re far from the end of their fight though they have sown the seeds for a brighter future.

Featured in the New Yorker